Taking daylight to the next level

Category

Best practice

Best use of Natural Light prize

Daylight & Architecture

Uncategorized

Author

Jakob Schoof

Photography

Nigel Young

Torben Eskerod

Share

Copy

In 2024, Foster + Partners won the Best Use of Natural Light prize at the World Architecture Festival in Singapore for the ICÔNE office building in Esch–sur–Alzette, Luxembourg. We spoke with Darron Haylock, partner in the architect’s office, about his design for the building.

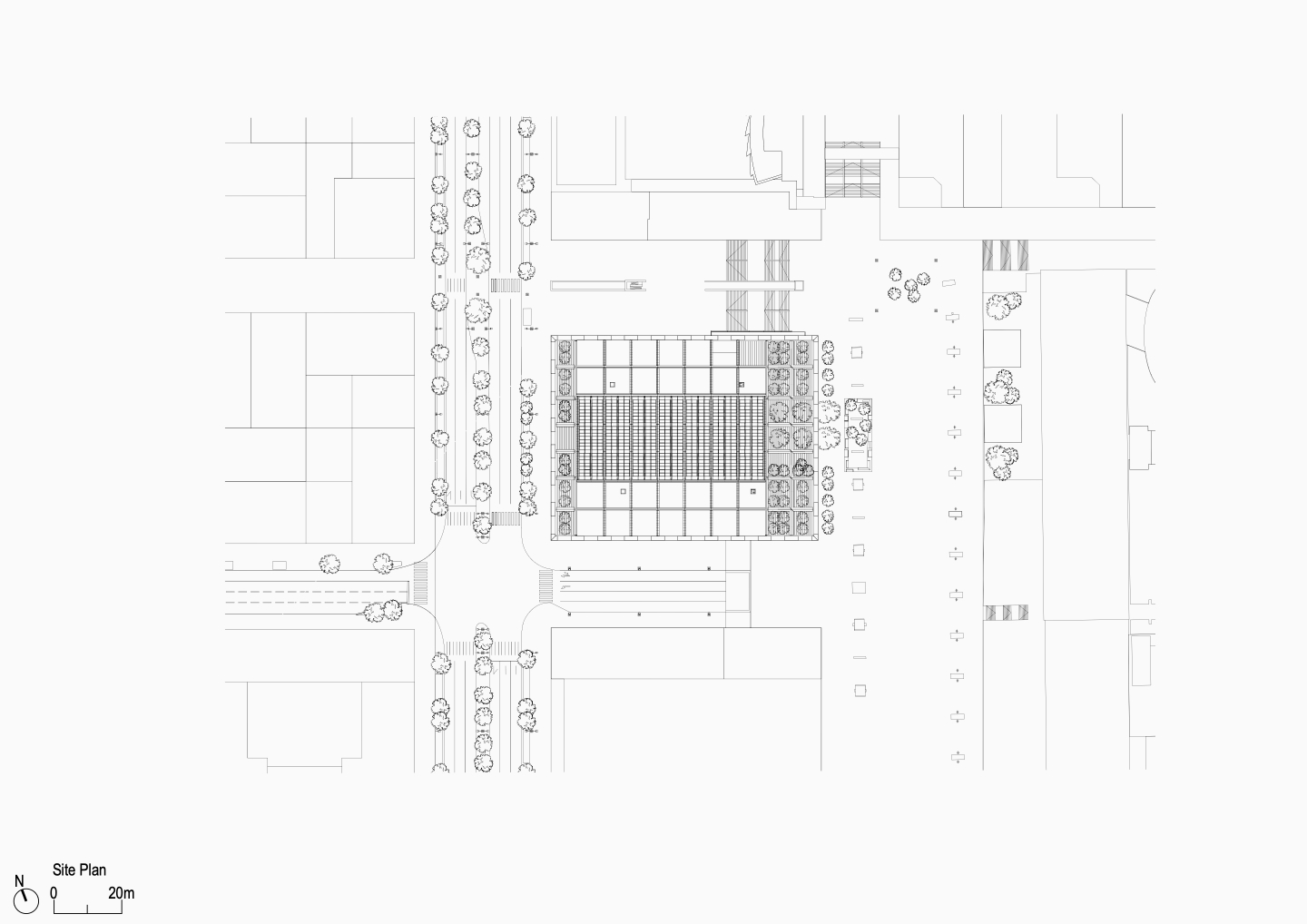

Esch-Belval was once home to one of the largest steelworks in Europe. Since its closure in 1997, the area in the far south-west of Luxembourg has become a thriving city of science. Its transformation, guided by Dutch architect Jo Coenen’s 2001 master plan, has generated a vibrant mix of research institutes, office buildings, a branch of the University of Luxembourg, shopping centres and residential blocks. Situated adjacent to the central square of the area, opposite the University Library and a blast furnace-turned-museum, ICÔNE embodies this blend of industrial heritage and modern innovation.

As a former industrial site, Esch-Belval has a strong character, characterised by a mix of industrial heritage and high-quality contemporary architecture. How did this influence your design for ICÔNE ?

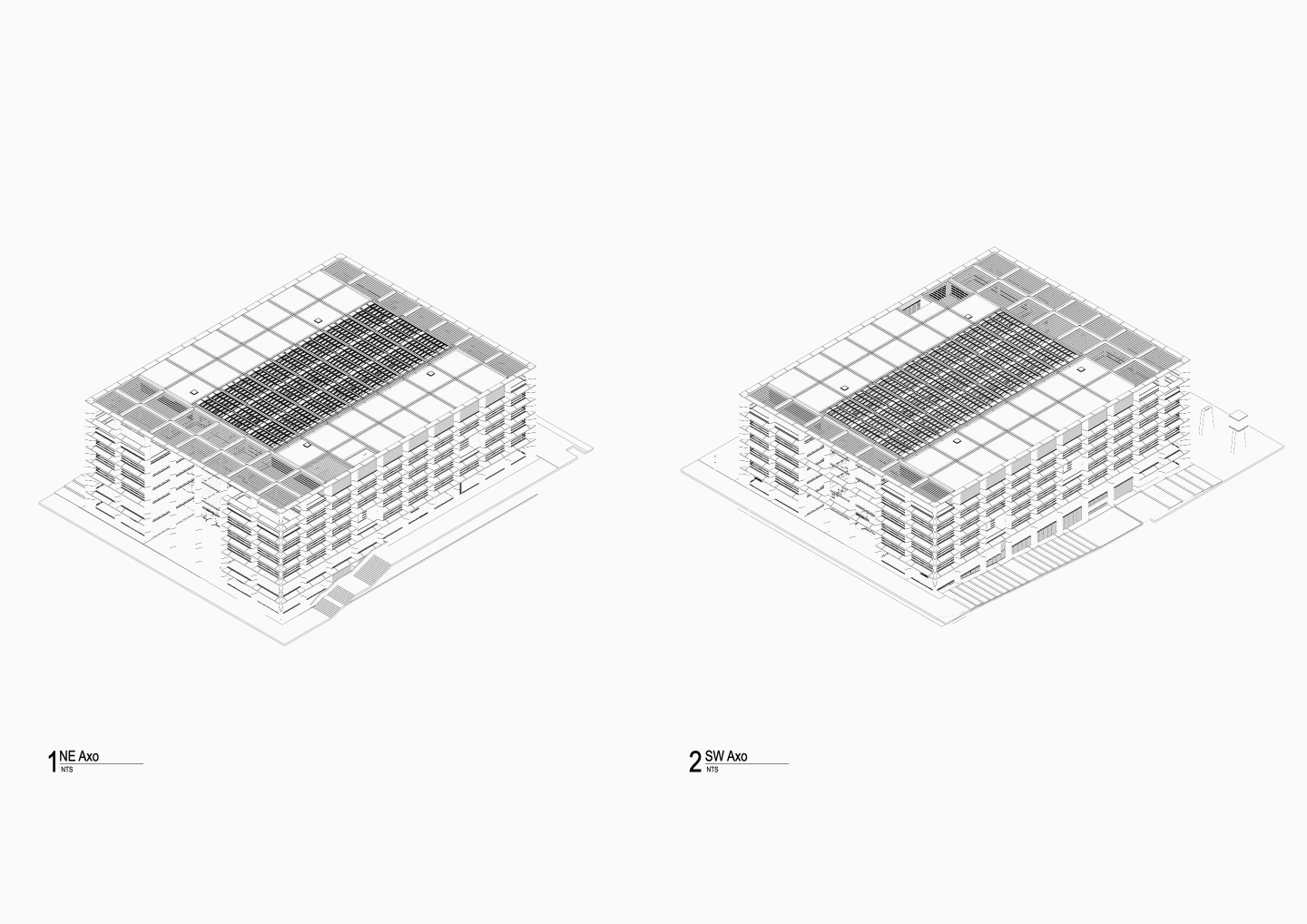

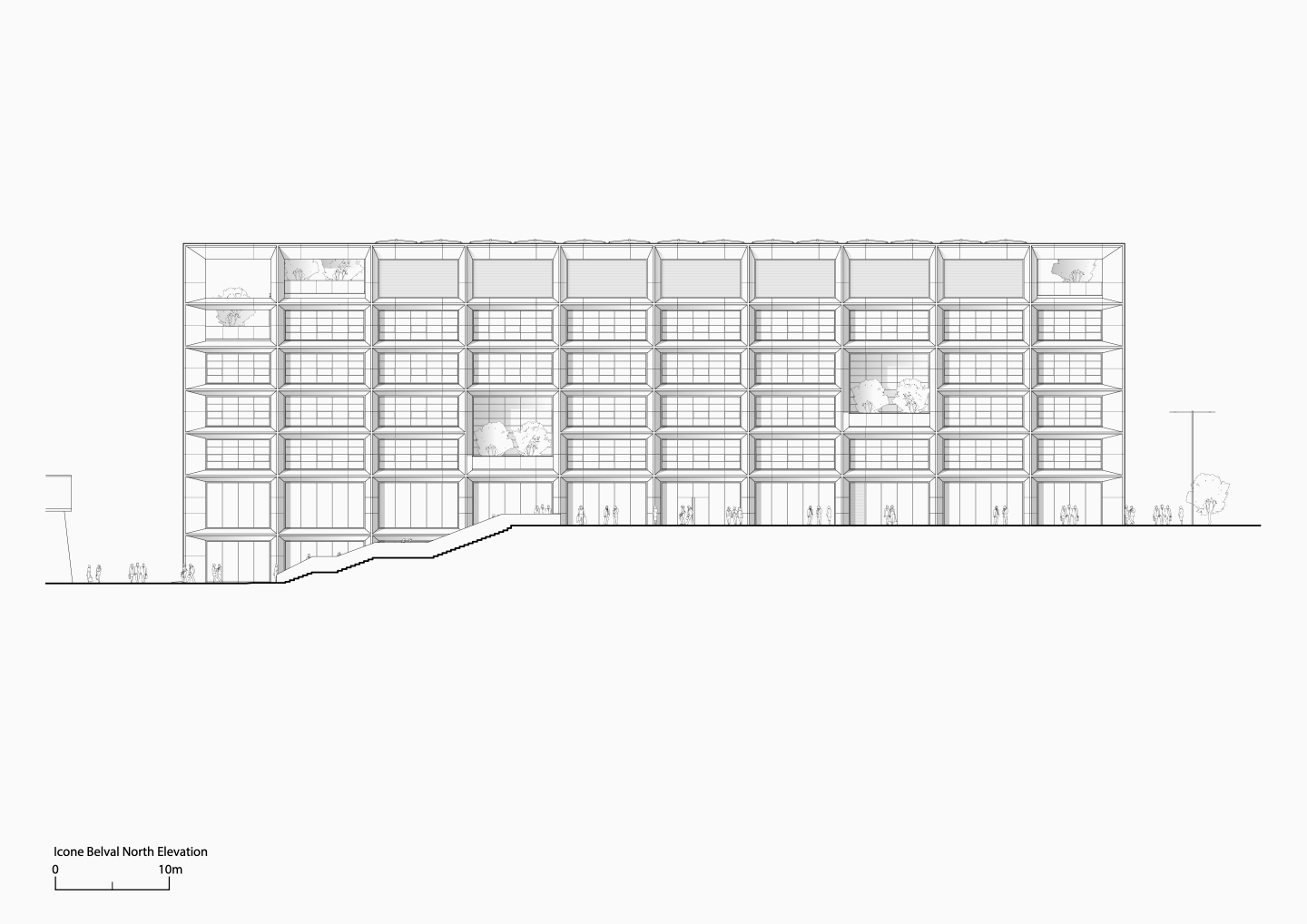

The site has a fascinating industrial heritage as a former blast furnace area, which became a natural design inspiration for us. We aimed to create a building that would both complement this historic setting while maintaining its own distinct identity. Our approach resulted in a very structured, controlled exterior architecture that’s honest in its expression from inside to outside. When addressing the site’s unique topography, we carefully considered how to bridge the level difference between Port of France in the west and the plaza level in the east. We wanted the building to serve as a connector, encouraging pedestrian flow through the space while maintaining a visual dialogue with the historic blast furnace.

The area still looked very different when you started the project in 2016. To what extent did the overall master plan for the area influence your design?

When developing this project with our client BESIX RED, we had two potential sites under consideration. We quickly gravitated toward this location because it offered both street presence for identity and a strong connection to the Belval community. We engaged extensively with the urban planners to understand their vision and objectives for the site. Through these collaborative discussions, we were able to ensure our design aligned with and supported their broader aspirations for the area’s development.

When you started the design, what kind of users did you and your client have in mind?

We originally conceived this as a speculative office building, so we did extensive analysis of potential tenants to inform both the architecture and help our client target the right market. Given the proximity to the university and the presence of financial institutions in the area, we focused on the fintech sector. Our plan was to create a co-working nucleus of about 5,000 square meters, potentially operated by a company like WeWork, that would energise the entire building. This hub would be surrounded by other tenants, with up to four tenants per floor occupying at least 250 square metres each. Eventually, the building ended up being 90% occupied by a French bank – however I’m pleased that our flexible design concept still works perfectly.

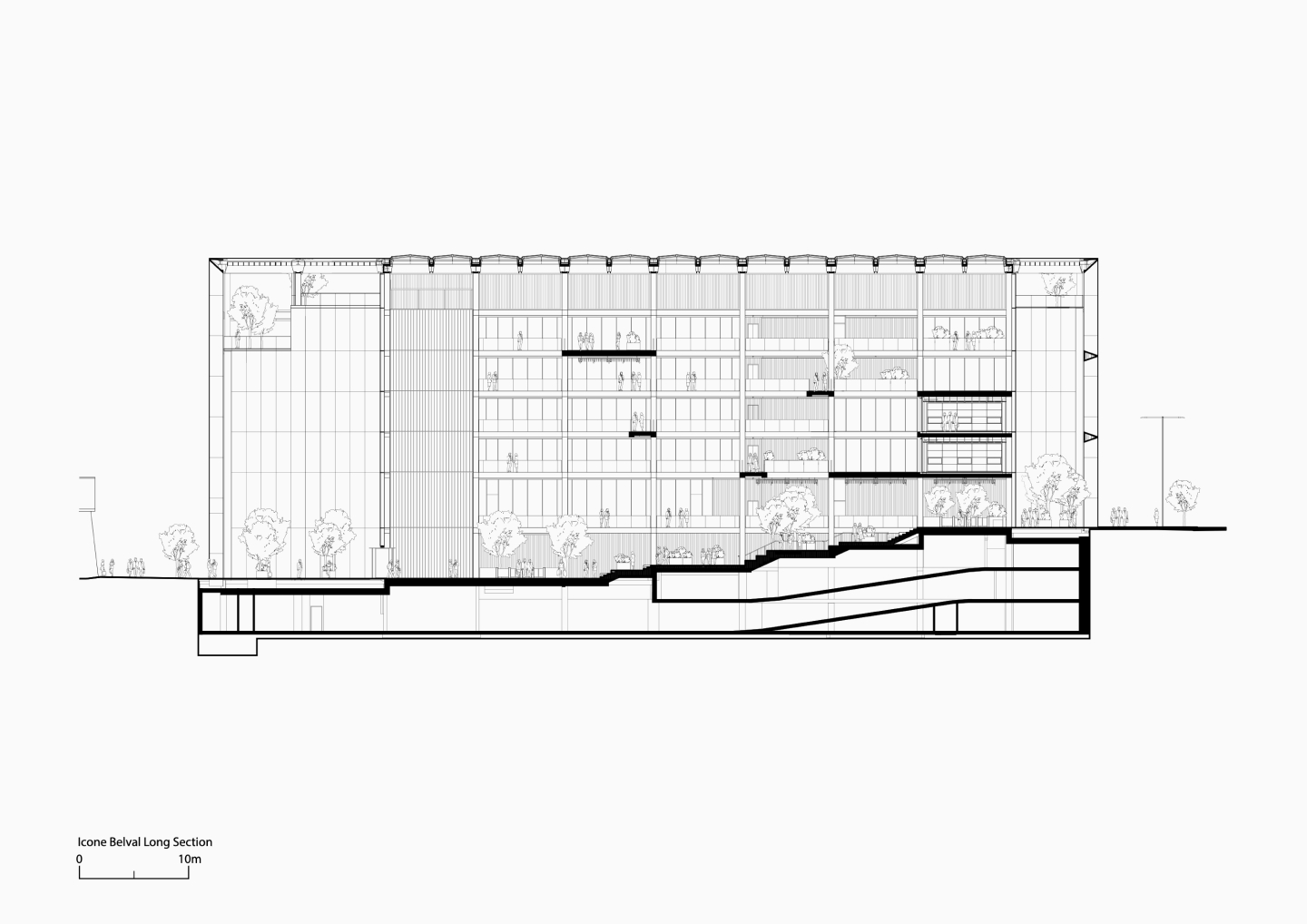

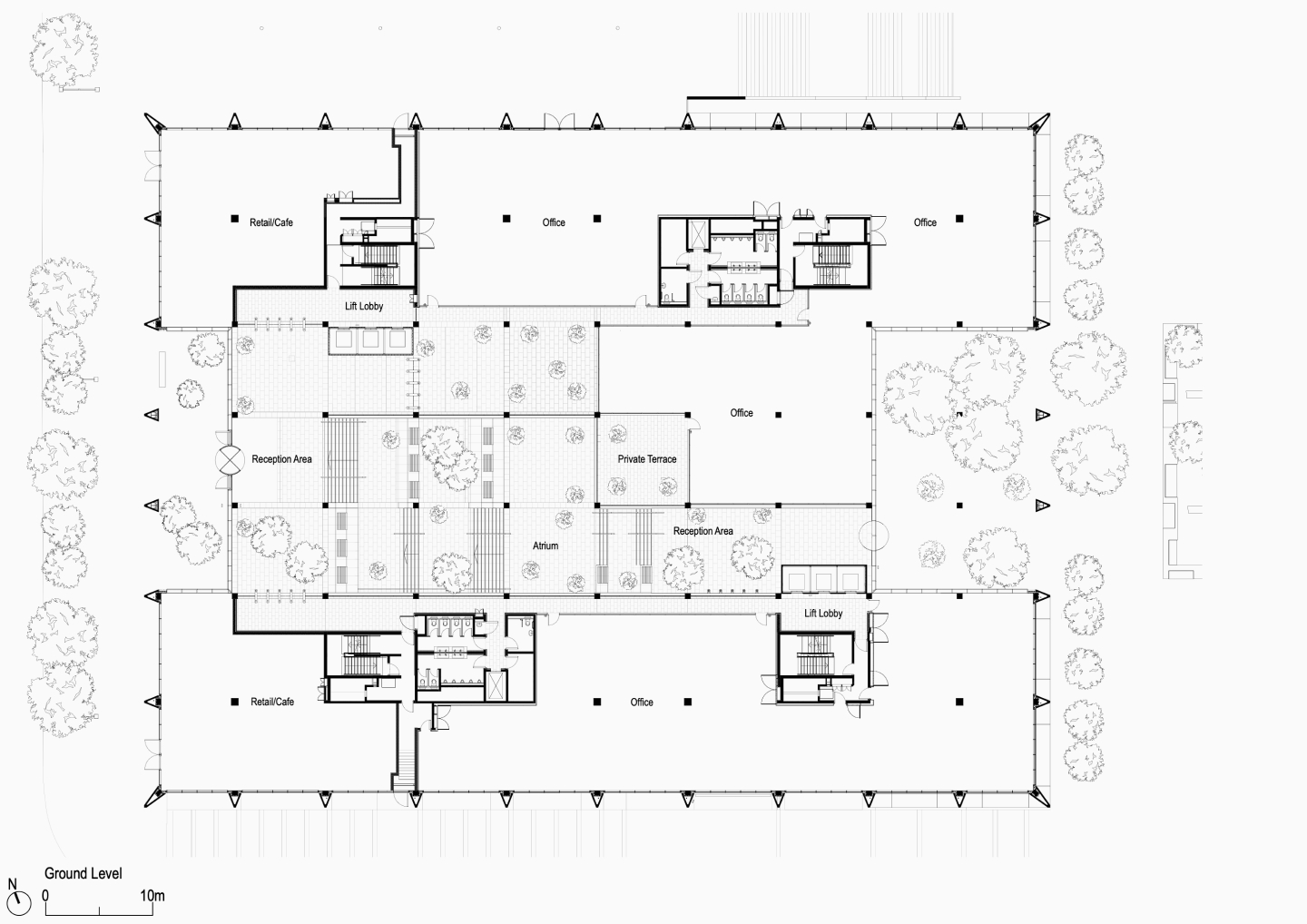

Entering the ICÔNE building reveals a breathtaking five-storey atrium that spans its entire length. Two slightly offset entrances create a sense of spatial tension, gradually revealing the atrium’s full dimensions as you explore. A wide series of steps connect the different entrance levels, accommodating the natural slope from Place de l’Académie in the east to the Porte de France street in the west. Above, slender concrete columns support the roof, adding structure and coherence. Unlike traditional atriums, this space is designed to be a lively meeting point and workspace, fostering interaction and creativity.

“We aimed to create a building that would both complement this historic setting while maintaining its own distinct identity”

How did you achieve the spatial flexibility you mentioned and the generosity of the open atrium, while still making the project financially viable?

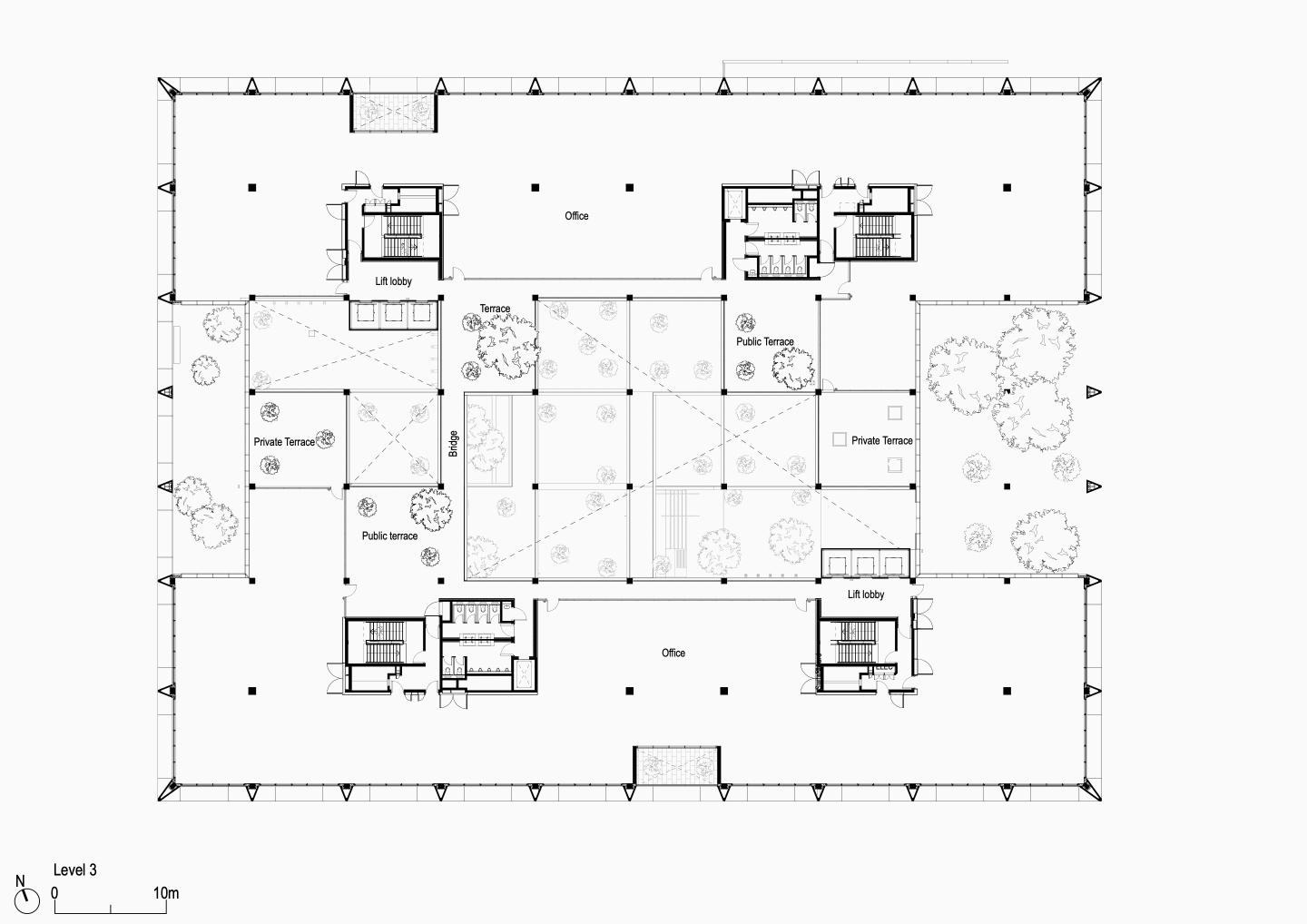

I have to give credit to our client for the spatial success of this project. They really understood and valued the importance of creating quality workspaces with good daylight and outdoor connections. Unlike many developers, they never questioned the ratio between rental and gross floor areas or criticised an excess of circulation space. They recognised that even non-traditional office spaces such as the open terraces could command the same rental rates if they are well-connected to office areas. We created a mix of terraced spaces – some directly linked to offices, others connected via bridges, serving as breakout and social spaces. The WELL standard guided our approach to wellbeing, ensuring good views, daylight, and biophilia. Once we developed and presented these ideas, the client was completely on board.

The atrium is unusually generous for a speculative office building. What did you want to achieve with this space?

Atriums are certainly common in office buildings for bringing in natural light, but we took the concept further here. Rather than creating a typical linear atrium, we broke up the edges and layered the organisation. While the floor plates are not particularly deep, we wanted the atrium to be a focal point that brings daylight down to the lower levels.

When my colleagues and I discussed it, we realised this building could accommodate about 2,000 people – coincidentally the size of our own office at the time of completion. With its visual connectivity between floors and departments, it would actually be perfect for Foster + Partners. This kind of transparency really supports our integrated design approach, and we incorporated elements we’d love to have – great breakout spaces, abundant daylight, views to the outside, and biophilia throughout. It’s interesting how our own workplace desires shaped the final design.

Plants play a key role in your concept for ICÔNE. Nowadays, they are an almost indispensable part of every office atrium. Why do you think that is?

The incorporation of plants was especially important given our mineral-heavy location near the former steelworks, where there is not much natural greenery. While we faced some challenges with daylight in such a large space, we worked closely with the landscape designers to select an organic mix of plants. The natural daylight was crucial not just for the people but also to sustain the plants and promote that sense of wellbeing.

What criteria did you use to select the plants in the atrium?

We aimed for variety in our plant selection, wanting to create a relaxed atmosphere while being mindful of maintenance requirements and budget constraints. Our landscape team helped ensure we chose appropriate plants to create a welcoming, green environment. There were no specific requirements – we just focused on making it as lush and inviting as possible.

“We carefully analysed air movement, while upper levels are naturally warmer due to thermal stacking, we ensured sufficient space above the last occupied floor for air circulation”

What type of glazing did you use for the atrium to encourage plant growth?

For the glazing, we used a special PVB interlayer between the laminated glass, which was crucial for plant growth. We learned from our experience with the Maggie’s, a cancer care centre in Manchester, that standard 95% PVB interlayers block important UV light needed for plants. This special interlayer allows the right type of UV light to penetrate while maintaining safety standards. Looking at the plants today, they seem to be thriving!

How is the atrium ventilated?

The atrium uses what we call assisted ventilation. Rather than opening roof lights, we extract air through louvres on either side at the top of the space. This system recirculates and moves air around in an economical and sustainable way while meeting fire control requirements. It’s naturally ventilated but with mechanical assistance, so it’s not entirely dependent on opening doors and windows.

The whole building is heavily glazed. How do you protect the atrium from overheating in the summer?

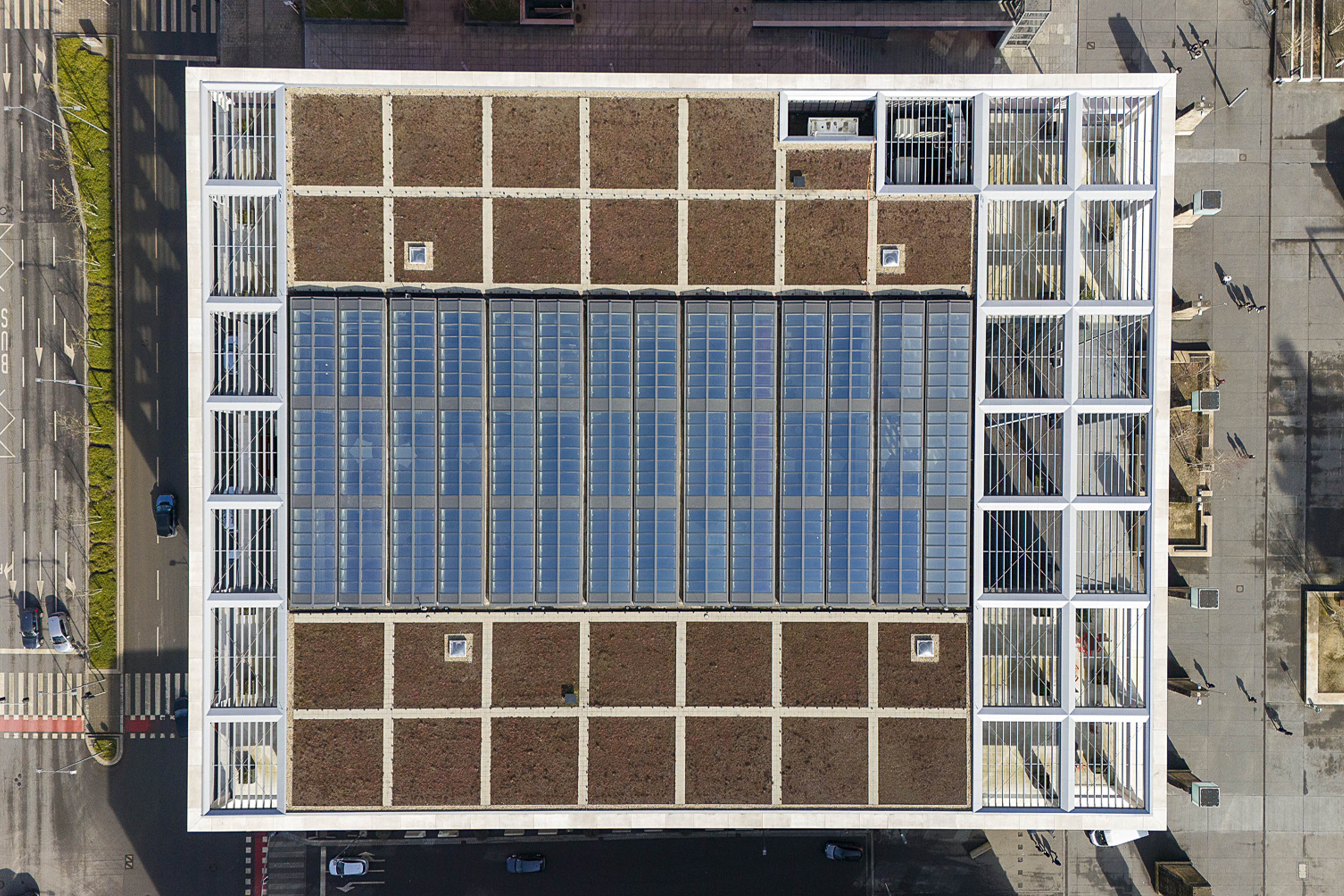

The sheer size of the atrium helps prevent overheating, along with a dot matrix pattern on the roof glass that reduces solar gain and helps conceal dirt. We carefully analysed air movement: while upper levels are naturally warmer due to thermal stacking, we ensured sufficient space above the last occupied floor for air circulation.

And how do you ensure the right balance between daylight and solar shading in the office spaces?

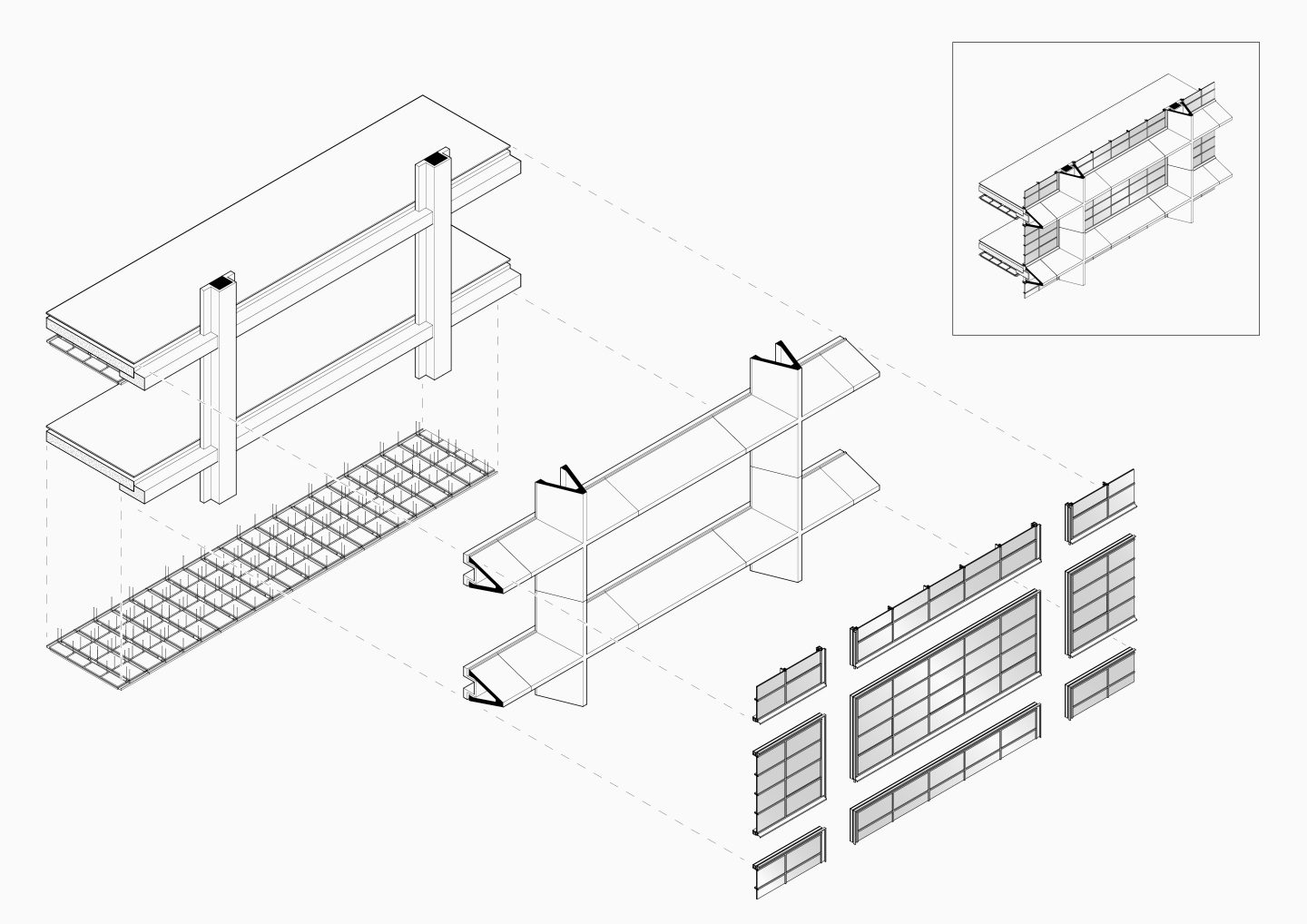

The external facade has significant depth at 1.35 metres, primarily due to the fin protection. Working with our engineers, we modelled how these fins could protect against unwanted solar gain from south, west, and east exposures while maximising beneficial daylight. Though we considered varying the facade depth around the building, our analysis showed only marginal benefits, so we maintained consistency for architectural purposes. We supplemented this with internal glare and privacy blinds to achieve an optimal balance between solar shading and natural daylight. The facade is naturally ventilated, allowing occupants to open windows.

With its spacious green atrium, ICÔNE is part of a long tradition at Foster + Partners. As early as the 1990s, the architects began designing atriums as green oases, not only to impress visitors, but also to provide staff with space for relaxation and creative inspiration. In addition to the classic ground-floor atrium, Foster + Partners soon experimented with multi-storey spaces in high-rise buildings. The Commerzbank tower in Frankfurt (1997) and the Swiss Re tower in London (2004) were pioneering examples. Over the years, architects have refined their repertoire to include atriums for almost every use and climate zone.

Last year, ICÔNE was awarded the prize for the Best Use of Natural Light at the World Architecture Festival in Singapore. What sets this project apart from other office projects in terms of daylighting?

You would have to ask the judges why they chose us for the award. However, what makes this building special is its honest use of materials – concrete provides structural stability while timber features prominently on walls, ceilings, and touchpoints, creating that crucial connection to natural environments. It’s a light, airy space that succeeds through the combination of thoughtful arrangement, maximised daylight, and carefully chosen materials.

“Over the last 30 years, office design has shifted significantly from the utilitarian layouts of the 1990s to more open and employee–centric space”

Looking back, what have been the main advances in office design over the past 30 years? To what extent are we designing different types of office buildings than in the 1990s?

Over the last 30 years, office design has shifted significantly from the utilitarian layouts of the 1990s to more open and employee-centric spaces. In the 1990s, offices were designed with a strong focus on functionality and efficiency. However, this layout often led to cramped and isolating work environments. Today, offices are designed with a greater emphasis on collaboration, well-being, and flexibility. Retaining staff has become crucial, and creating an environment where people want to work is key. This means designing spaces that inherently support well-being and are part of the building’s DNA, not just relying on

fit-outs.

Recently, the COVID pandemic has indeed made these aspects even more relevant. Natural ventilation, for instance, has become more popular and easier to communicate to clients. Allowing users to control their environment, like opening and closing windows, has become increasingly important.

What role do post-occupancy evaluation studies and the evidence they provide play in your work?

Post-occupancy evaluation studies are invaluable to our work. We have done them on several buildings, including ICÔNE, where we plan to do one this year. These studies help us to understand not only the technical performance of a building, but also its social performance. They provide insights into how we can improve the environment, make the building more efficient and manage it more sustainably. For example, we have learned that it’s important to turn off the lights at night to allow the plants in the atrium to regenerate, something that might not be immediately obvious. In a transparent building like ICONE, with its impressive atrium, tenants are naturally inclined to leave the lights on all night.

Darron Haylock joined Foster + Partners in 1995, after graduating from De Montfort University in Leicester. He has worked on a variety of projects from Healthcare in the UK to tower projects in Israel. Quality and clarity of design is central to his projects, and he likes to explore design options through sketching.