From Intuition to Evidence: Architecture in the Age of Data

Category

Daylight

Daylight & Architecture

Research and Innovation

Author

DAVID BASULTO

Photography

SIMON KLEIN-KNUDSEN

NIGEL YOUNG

LACATON & VASSAL

ATMOS LAB

FOSTER + PARTNERS

Share

Copy

With the rapidly growing challenges in our environment and society, our buildings have become key for human and planetary health. Architecture is no longer about static structures; it is about dynamic, measurable systems that shape how we live, breathe, think and heal. The 10th VELUX Daylight Symposium in Copenhagen, held under the theme “Towards Healthy, Resilient and Sustainable Architecture,” made this shift tangible. The long-standing triad of practice, industry and research comes closer together, turning design intuition into proven, validated actions within a continuous, accelerating loop of knowledge transfer.

We find ourselves designing in sync not just with nature, but with our own biology. The circadian system, once the concern of neuroscientists, is now an important design parameter. Architecture becomes dynamic again as it performs not just in space, but throughout time.

THE PUBLIC HEALTH TURN: FROM INTUITION TO EVIDENCE

Perhaps the most radical shift the symposium revealed was the repositioning of buildings as public health infrastructure. Joseph Allen, from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Director of the Healthy Buildings Program, described this as a “paradigm change” only accelerated by the recent global COVID-19 pandemic. His five “fundamental shifts” reframed the built environment as a living determinant of wellbeing inside buildings, from mechanical enclosures to living systems. He outlined five interconnected shifts: Paradigm – understanding and visualisation of carefully designed airflows; Policy – setting ventilation targets; Awareness – from ignorance to understanding of how data reveals the cognitive and economic value of clean indoor air; Measurement – empowering occupants through affordable sensors; and finally, from aspiration to Action as we realise that healthy, sustainable buildings are not ideals, but achievable realities we can put into practice.

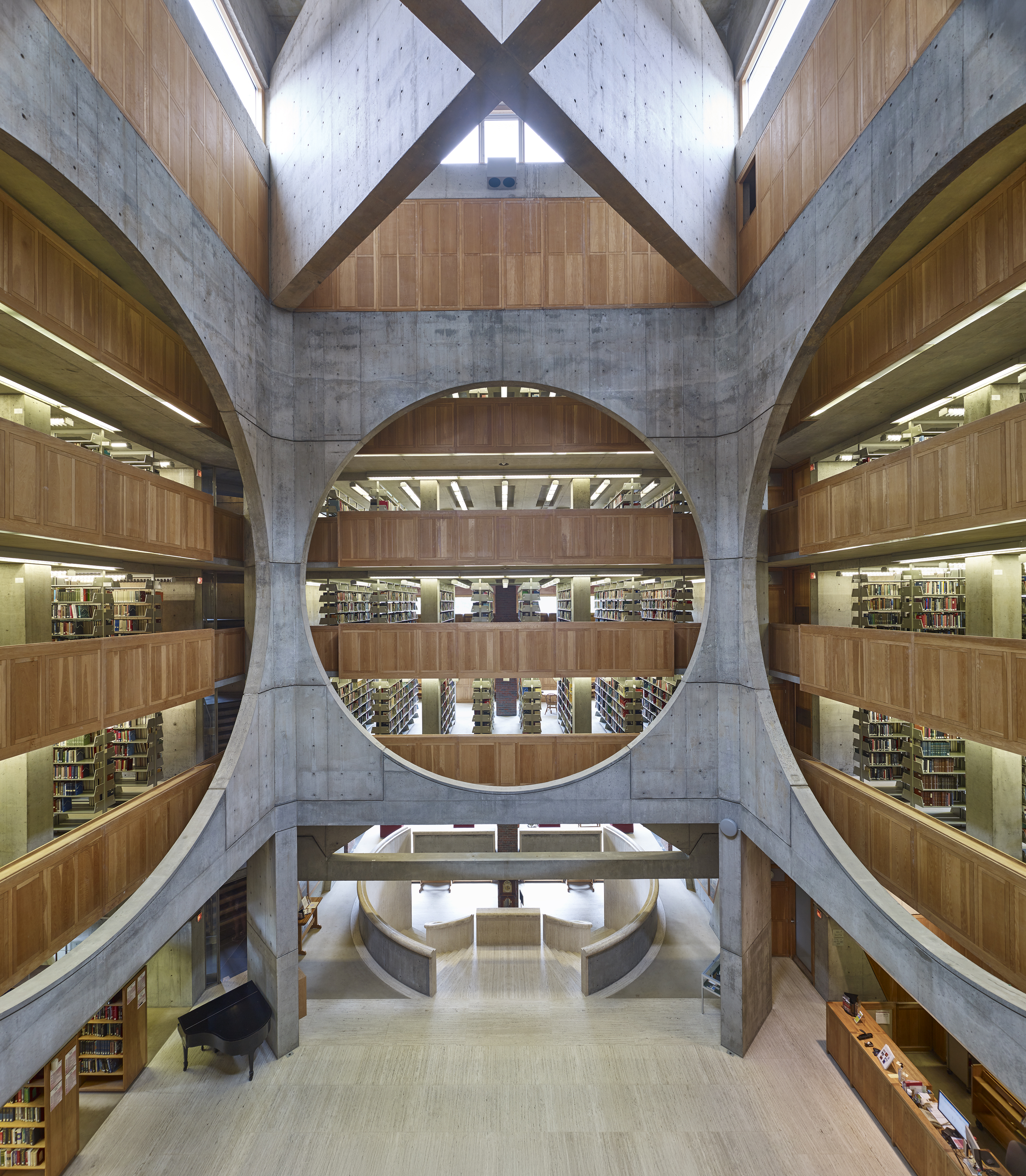

This demand for validation echoed throughout the symposium. Darron Haylock of Foster + Partners illustrated how architecture is evolving from intuition toward evidence without losing imagination. He spoke of the Apple headquarters at Battersea Power Station, a project where daylight and artificial lighting systems are synchronised to mirror the circadian rhythm of the outside world. “The lighting responds to the daylight outside using sensors,” he explained, “allowing fittings to adjust throughout the day, extending the sense of connection to the sky.” For Apple, exchanging usable floor area in exchange for deeper atriums and more daylight was not a sacrifice but an investment. The building, Haylock noted, “behaves like an advanced machine,” continuously calibrating its light environment, as responsive as the screen of today’s smartphones.

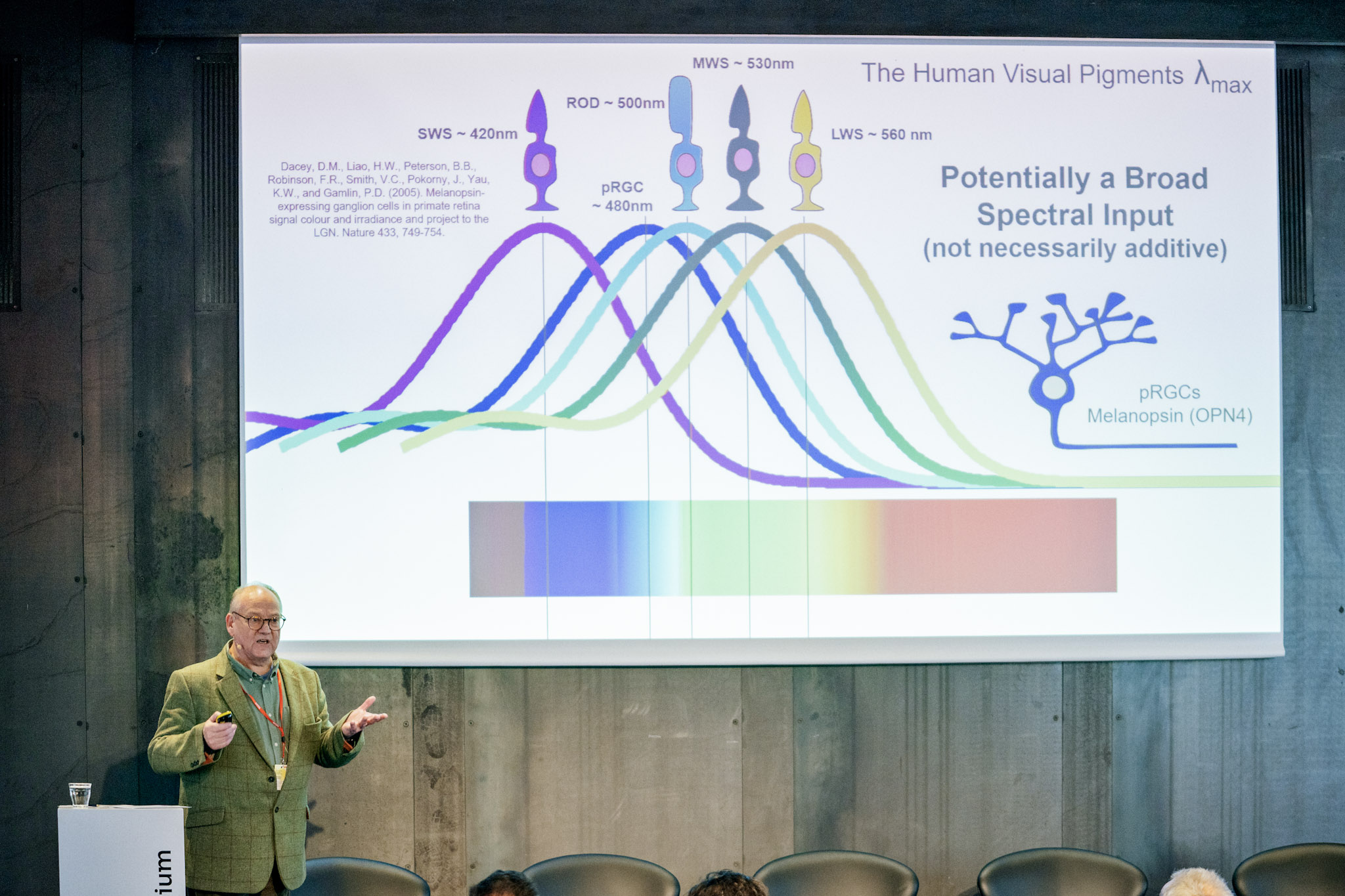

At the other end, Russell Foster, the Oxford neuroscientist whose discoveries underpin much of our understanding of the human circadian system, offered the biological context. His research on the human circadian system shows how the eye’s light-sensitive cells regulate sleep, mood and cognition through exposure to natural light. Light, he reminded us, is medicine as much as medium. “What we do with our buildings has the potential to be the greatest public health intervention of this century,” Foster said. Together, Haylock’s responsive building strategy and Foster’s cellular science converged into the single concept of architecture as an active agent regulating human physiology.

Its effect can also be understood from Dr. Eleonora Brembilla’s research, as she warned that society is suffering from light deprivation. The global myopia epidemic, expected to affect half the world’s population by 2050, is not simply genetic; it is environmental. People are spending too much time indoors and not receiving the minimum two hours of daylight our biology requires. Building form, glazing technology and urban design must now compensate for our modern lifestyle. The crisis of light is, fundamentally, a design crisis.

BEYOND COMFORT: RESILIENCE AND THE HUMAN PERCEPTION

If health data provides new reasons to design better, resilience gives us a new way to understand comfort. Marcel Schweiker of RWTH Aachen challenged the long held pursuit of constant equilibrium. “Relief, encouragement, joy,” he said, “these come from variation, not stasis.” His research shows that small doses of thermal or visual discomfort can train the body’s adaptability. The most resilient occupants are those who understand and can influence their surroundings. The over-automated building risks producing learned helplessness, a state in which a person stops trying to influence their environment after repeated experiences of having no control.

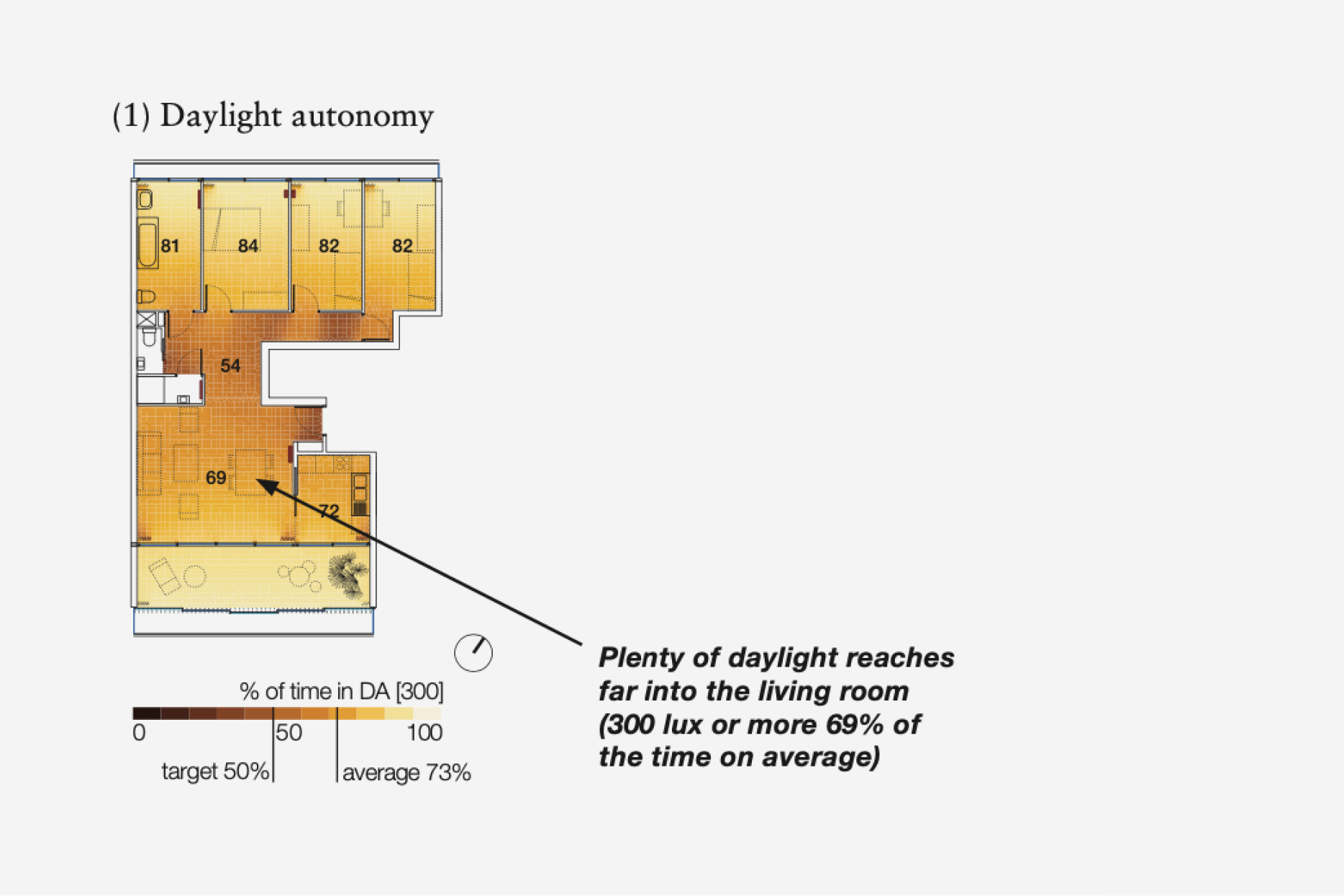

Florencia Collo of Atmos Lab expanded the discussion from human adaptation to architectural intelligence. Her multi–year post occupancy research on Lacaton & Vassal’s Grand Parc in Bordeaux showed how careful design, rather than high technology, can produce stable, comfortable environments with minimal active energy use. Through long-term monitoring, her team measured how the building’s winter gardens act as climate moderators, maintaining temperatures between 15 °C and 19 °C in winter simply through envelope section, material and light. But her contribution went beyond performance data. She reminded us that refurbishment is a model for the future; architecture that restores, rather than replaces, and that learns from the climate instead of resisting it. “Don’t fight climate, use it,” she concluded.

In this human-scaled ecology, Özge Karaman-Madan added a sensory dimension. Her research quantified how moving, dappled light resulting from the shimmer of leaves that produce the slow drift of shadows, restores cognitive function more effectively than static illumination. We evolved with light that moved.

Together these perspectives redefine comfort as rhythm: a movement between exposure and protection, stability and change. As Schweiker suggested, our task is not to eliminate stress but to choreograph it.

PERCEPTION, VIEW AND THE CIRCADIAN

Lisa Heschong, whose pioneering research linked windows and learning outcomes over decades, returned with a new vocabulary for the emotional side of circadian design. She described windows as providers of “circadian snacks,” those unconscious glances to the outside seeking the natural light we need for our internal clocks. The “magic of views places us in time and place,” she opened. Daylight and the horizon act together as anchors for the mind’s wandering, feeding the brain’s creative default network. Heschong also raised a new concern: high-performance glazing, while efficient, may filter out up to 90 % of certain blue-light frequencies essential for this to happen.

Michael Kent from Singapore University of Social Sciences extended the argument into data. View quality, he noted, depends not only on content but also on clarity and access. Dynamic shading systems, if poorly tuned, can destroy the very connection they aim to optimise. Between Heschong’s poetry and Kent’s parameters lies the next challenge: to quantify delight without extinguishing it.

Both speakers reframed daylight as nourishment, a rhythm our bodies crave. As Foster’s biology confirmed and Haylock’s Apple project demonstrated, the circadian pulse of light is where performance and pleasure meet.

TECHNOLOGY AND THE ACCURACY CRISIS

Every discussion of evidence demands a discussion of its reliability.John Mardaljevic from Daylight Experts exposed the uncomfortable truth behind our simulation tools: the data driving most daylight models are synthetic, based on composite typical meteorological years that never actually occurred. Designing for resilience on such data is challenging, especially in an age of climate volatility. He advocated the use of satellite derived climate data, like CAMS records, to ground daylight modelling in real observations rather than synthetic averages.

Towards the end of the sessions, Claus Madsen and Ivan Nikolov of Aalborg University addressed one of the big questions of the symposium – the possibilities of AI. Their research tested how generative image models visualise daylight in architecture, comparing and combining different models. The results were as exciting as they were flawed. The images were enticing but inconsistent, sometimes inventing walls or closing openings entirely. AI, they concluded, can imagine light but not yet simulate it. Still, they see potential in a hybrid workflow: pairing precise modelling with intuitive AI visualisation could make evidence-based design more accessible. We might be closer to a future where building simulation becomes democratised, faster, and user-friendly.

At the urban scale, Zhang Li from Tsinghua University offered a glimpse of this integrated future through his concept of urban ergonomics. By combining physiological data with spatial simulation, his team studies how people perceive underground or artificially lit environments, using moving shadows to simulate the passage of time and calm those deprived of natural light. His work turns data into empathy, a bridge between measurable metrics and emotional experience.

A PHILOSOPHICAL SHIFT

During the symposium, we witnessed an evolution in architecture not just driven by technological advancements, but changes in how we conceive architecture. We are moving from a reactive, compliance-driven practice to a proactive, evidence-based craft. The future of architecture lies in a philosophical shift: from designing for comfort as an end state to designing for capability, thus enabling enable humans and buildings to adapt, learn and thrive.

As Zhang Li observed, science may offer clear data, but design remains a “blurry art.” The architect’s task is to interpret that data with judgment, empathy and courage, to know when to maintain the comfort zone, when to welcome variation and when to simulate realities that are yet to come.

Technology will accelerate this integration. The goal is a digital life cycle where information flows seamlessly from research to design to occupation. To reach it, we need high fidelity data tools that are as intuitive as the devices we use daily; the smartphone equivalent of building simulation, closing the feedback loop between experience and evidence.

We have long designed for comfort; now we must design for comprehension. We must design in rhythm with the planet, with light and with the beating pulse of human biology.

In the age of data, intuition still matters. But it must now be driven by evidence, guiding us toward an architecture that is not only seen and inhabited, but truly lived.

Find out more about the Daylight Symposium and watch all presentations here.