Illuminating North, Light as Metaphor and Deep Ecology

Forgive me, it is a banal observation, but light is not just what we see by. It is how we see. As part of the 2023 UIA World Congress of Architects in Copenhagen, Daylight and Architecture hosted a “Daylight Talk” by Dorte Mandrup. In the presentation and talk, Mandrup unfolded the meaning and doing of light in mainly three projects: The Whale, Kangiata Illorsua (The Ilulissat Icefjord Centre), and The Wadden Sea Centre. It became obvious to the viewers that in the world of architectural form giving by Mandrup, the intricate relationship between the world as it presents itself to us (as context and the play of light) and how we wish to shape it, is an omnipresent challenge no matter the site and project. But in the three projects mentioned, there is in a very profound sense, an ongoing exploration of the potential of light in the articulation of architectural possibilities.

Dorte Mandrup’s awareness of the meaning of light conditions as context rests on a very unsentimental observation; it is in essence scientific or driven by what comes out as what could be called a fascination with the facts of materiality. Then, in the process of form giving this initial registration of matter is turned into spatial poetry of almost hyperawareness to the effects and meaning of light of the specific site. In the world of facts, light is both particle and wave. It is matterless, but at the same time materially consequential. It defines visibility, it animates colour in our world, ultimately measures time, and is the stuff that binds the visible cosmos together. To us, and therefore in architectural space, it is at once familiar and elusive and as such, light is one of both nature’s and architecture’s most paradoxical phenomena: intangible in form but foundational to perception, essential to life yet mindbogglingly abstract in its nature.

“To speak of light is to speak of thresholds: between presence and absence, wave and particle, now and then, seen and unseen.”

The Matter of Fact of Light

From a scientific perspective, light is simply electromagnetic radiation – a fluctuating field of electric and magnetic forces that travels through space. The human eye perceives only a narrow band of this spectrum. Beyond this visible sliver lies the ultraviolet, infrared, radio waves, X–rays, and gamma radiation – each obeying the same physical laws but largely inaccessible to our sensory perception.

What makes light singular in physics is its duality. Since the early 20th century, quantum mechanics has revealed that light behaves both as a wave and as a stream of discrete energy packets known as photons. This dual nature resists simplification. It is the poetry of physics. And in the world of Mandrup, light is obviously more than just a physical phenomenon, light is also a vector of meaning. It sculpts space in architecture, as well as it gives form to vision in biology, and serves as metaphor in philosophy, theology, and art. Photons may be massless, but their cultural weight is immense. In scientific, as well as architectural inquiry, it is the basis for observation, the very condition of visibility. Without light, there is no architecture. In cosmology, light acts as a messenger from the past. When we observe a distant star, we see it not as it is, but as it was millennia ago, a fossil imprint of time. It teaches us that light is not only illumination, but also memory written in waves. To speak of light, then, is to speak of thresholds: between presence and absence, wave and particle, now and then, seen and unseen. It is at once the most elementary and the most enigmatic phenomenon in nature – a force that shapes the world and the way we apprehend it. In practical terms, light enables life on Earth: it drives photosynthesis, regulates biological rhythms, and forms the basis of sight. In a more philosophical sense in our understanding of architecture, light represents clarity, and revelation, and in a certain way, knowledge and inspiration. We do not merely use light to see the world, we interpret the world through the lens that light allows. In this particular way, light is obviously a natural phenomenon translated into a sensory experience through forgiving, but it is equally a metaphor of the Northern context, an identity even that can be used as the starting point of architectural explorations. Being brought up in the North, we develop a distinct relationship to light, the need and want of light after a long winter, the joy of the light emerging in the spring, the orientation of building towards the light and how we settle in the landscape to harvest light as a resource.

In the green transition of the building industry, it is more obvious than ever, that light is not only the vessel of architectural imaginaries and sculpting, but one of the fundamental, in a very pragmatic sense, resources we have. If it is carefully applied, it will not provide only aesthetic and sensory stimuli and elevate the spatial qualities of a building and site, but act as an agent of change in the quest for more climate resilient and responsive architectural formulation. It becomes a vessel of deep ecology and connection to our surroundings, the world we inhabit for such a breathtakingly short time. It manifests itself as an architecture of presence, or interpretation of genius loci, the inherent character of space, to a very large degree defined by the light environment of the specific context at hand.

Mandrup’s buildings respond to these unique light conditions of the Northern Hemisphere not by fighting against them but by embracing their distinctive qualities. Whether working with the diffuse overcast of Denmark, the harsh yet finely outlined light contrasts of low sun Greenland, or the water–reflected light of Norway, Mandrup creates architecture that is intrinsically of its place. Consideration of form, material, texture, and sequence transforms the buildings into instruments that measure and reflect the ephemeral qualities of northern light.

Adventures in Deep Ecology

In a sense, buildings filtrate the light through openings in the building structure, through passages, and the interplay of volumes, allowing light to pass or diffuse. Through the opacity of materials, some closed off by their thickness, others offering an openness and acting like a membrane, allowing carefully measured doses of daylight into the building. The subtle light/shadow effects in the thatched roof/walls and overhang of the Wadden Sea Centre reflects and absorbs the light creating an array of ever–changing poetic effects. In the descriptions of the moving snow in Greenland where the wind carries the snowflakes restlessly around, as they are each small prisms reflecting the light, and the short sunrise and sunset in January as cause for celebration as life–bringing events unfold with the coming of a new season of light. The low–angle sun, blue shadows, and red light from the west register the movement of the day. It seems to me that Dorte Mandrup is a sort of spatial scientist with a profound understanding of the intricacies of the natural world, turned architect. The framing of the projects in the lecture is based on a reading of context inspired by the knowledge and insights derived from the longstanding dialogue and mutual exchange with scientific thinking. But the kind of scientific thinking that enhances not only our understanding of the facts of things but the poetics and depth of knowledge of the world. At a certain point, scientific descriptions of the world reveal themselves as a poetic of space. In that exact point, architectural understanding of the world and context overlaps with scientific matter–of–factness. In the description of The Whale, Mandrup brings in the geology of the seabed, the gorges that stretch under the ocean surface that help whales navigate. A fascination point that allows for time and horizon to be stretched. And to add to the drama, the gulfstream warming the climate as opposed to the arctic climate of the Ilulissat Icefjord Centre. To the non–architects listening, like myself, Mandrup provides an opening and a common ground for us to reflect on and participate in the grounding of her architectural thinking and doing. In these shared reference points outside the spatial vocabulary of architecture, the many motives and solutions presented are summarised and shared.

“We do not merely use light to see the world, we interpret the world through the lens that light allows.”

In my humble opinion, it seems as if Mandrup tries to consolidate us with both a scientific, and factual understanding of light as a phenomenon with the poetics of daylight – and even darkness. In Mandrup’s own descriptions/characterisation of contexts, there is a deep connection to the deep time of geology. It offers a holistic approach to the concept of context, and especially light. In the industrialised building culture the hierarchy of light has been turned on its head. Artificial light has been introduced as a way of erasing our sensibility to natural light and rhythms of the climate – a one size fits all season attitude towards light. In the challenging light conditions of the Northern Hemisphere, Mandrup has developed a profound understanding of how to harness, manipulate, and celebrate light as a fundamental element of architectural design. The work demonstrates that context can serve as the genesis of creative process, resulting in buildings that respond sensitively to their environments while creating spatial experiences through the thoughtful orchestration of light.

Condition: The Northern Light

Mandrup emphasises in her exploration of the contextual capacities of light, that in northern latitudes, light arrives at lower angles, contains less blue diffusion due to the greater distance from the sun, and travels through an atmosphere with fewer particles, especially in Arctic regions. This creates expansive skies and a sense of infinite distance perception. The quality of light – its diffusion, rhythm, and colour temperature – varies dramatically with geography, season, and time of day. In that sense, learning to read the light becomes not merely about illumination, it is about presence. As Mandrup notes, the Danish concept of “nærvær” (presence) permeates the projects as an overarching ambition to connect with the site through both rational analysis and poetic interpretation. This heightened awareness of being present in a place is achieved through the manipulation of light, activating our senses, creating architecture that engages with empathy as well as the abstraction of the cultural product architecture is, based on a scientific outlook and worldview.

The Wadden Sea Centre: Texture and Diffusion

In The Wadden Sea Centre project, the approach is to working with the diffuse, constantly changing light of the horizontal coastal landscape of the western regions of Denmark. The horizontal landscape is interpreted in the sculptural layout of the building and the long lines of the facades, overhang, and roofs that create shadow effects emphasising the dimensions of the building. Mandrup employs thatched reed –a local material –not only for its ecological appropriateness but for its remarkable light– responsive qualities. The texture of the hand–worked thatch creates a façade that transforms continuously, reflecting the shifting overcast sky that dominates the weather patterns. Mandrup explains that “two–thirds of the time you have an overcast on the sky,” resulting in diffused light that changes throughout the day. The thatch material captures these subtle variations, acting as a visual barometer of atmospheric conditions. In the extended blue twilight of Nordic summers, the building reads as a dark silhouette against the sky – a deliberate play on the region’s light cycle. Inside, Mandrup uses diagonal spaces and strategic roof lights to capture and reflect daylight, creating a counterbalance to the exhibition media. The building’s courtyard provides a wind–sheltered microclimate while maintaining the critical connection between interior and landscape,–between controlled and natural light.

Kangiata Illorsua (Ilulissat Icefjord Centre): Light and Movement

Three hundred kilometres north of the Arctic Circle in Greenland, Mandrup confronts the light conditions of the high Arctic at the Ilulissat Icefjord Centre. Here, light operates in dramatic counterpoints: the rich red–gold of low–angled sun versus the intense blue of shadows, the darkness of winter against the perpetual daylight of summer, the blinding white of snow fields versus the deep blue of the ice fjord. The building’s boomerang form responds to these dynamics by creating a processional experience of light revelation. Visitors move through a carefully choreographed sequence of spaces where triangular sections transition to rectangles and back, controlling views and light exposure. The building becomes an instrument that measures light’s passage, culminating in the revelation of the ice field – the ultimate expression of Arctic light reflected and refracted through ancient ice. Most poignantly, the building celebrates the return of the sun on January 12th after the polar night – a 40–minute appearance that becomes part of community celebration. In winter darkness, when the sun disappears entirely, the building works with the quality of moonlight reflected on snow, like a ghostly illumination.

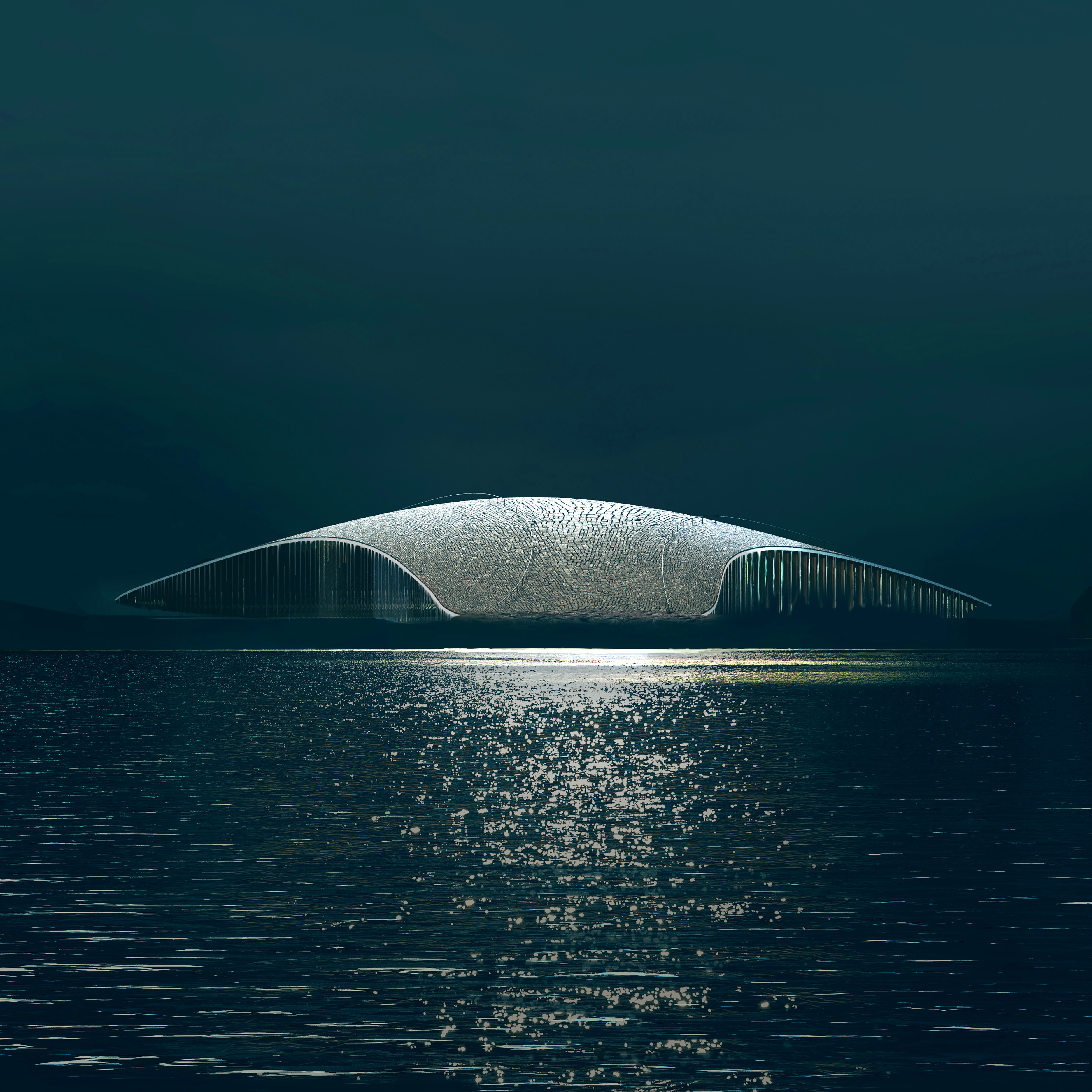

Reflection and Water: Light in the Whale

At The Whale Cultural Centre in Norway, Mandrup explores a different dimension of the specificity of northern light. The building cuts into the coastal landscape, appearing to emerge from the earth’s crust while using proximity to the ocean to capture reflected light from the water’s surface. This water–reflected light creates soft daylight bouncing onto the shell–like ceiling of the interior space. Mandrup notes the profound cultural significance of this water–reflected light for Scandinavians. The building purposely avoids creating a hard edge between land and sea, instead allowing the threshold to blur as water approaches the structure, maximising the capturing of this distinctive reflected light. The result is interior spaces that breathe with the rhythms of the ocean – showing the rippled patterns of light reflected from moving water.

Darkness and Contrast

While most of Mandrup’s work is devoted to understanding and even celebrating light, there seems to be an acknowledgment of the importance of darkness as a counterpoint. In the unbuilt project Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Centre, Mandrup deliberately worked with darkness to emphasise the gravity of the site’s history.

“Darkness needs light to be dark,” she observes, “and vice versa. Full darkness is not interesting.”

This understanding of the dialectical relationship between light and darkness reveals a nuanced conception of form giving. Rather than simply maximising illumination in the project, Mandrup orchestrates light’s presence and absence to create emotional and sensory experiences. This allows for an architectural philosophy that exactly treats both light as material and metaphor at the same time. An architecture that demonstrates that when architecture responds with sensitivity to local light conditions, the result is not just illuminated space, but buildings that connect deeply with human experience and natural cycles. As Mandrup succinctly states:

“Context is king – or queen – because everything we do is deriving from the context that we’re working in.”

In the northern latitudes, that context is defined by a variable light that Mandrup has mastered as few architects have.

Watch the Daylight Talk ‘Northern Light’ by Dorte Mandrup presented at the UIA World Congress of Architects 2023.