Inside the Light: Phillips Exeter Academy Library

Category

Daylight & Architecture

Design Philosophy

Author

PER OLAF FJELD

Photography

CEMAL EMDEN

Date

26/06/2025

Share

Copy

Over the years, there are a number of buildings I make an effort to visit whenever possible. Though some are ancient, others from the last century, and a number are Louis I Kahn works, each reveals a unique natural light situation set by structure. These two factors are the reason why I am never disappointed and equally invigorated by each visit. In relation to this article, choosing one Kahn building over another was a difficult task, since it is impossible to separate his work from the importance of daylight so deeply embedded in the core of Kahn’s creative process. I followed my initial intuitive choice and landed on Phillips Exeter Academy Library located in the small town, Exeter, New Hampshire, USA.

The reason for this choice goes back 52 years in time to 1973. I had just graduated from Kahn’s Master Class at the University of Pennsylvania. The Phillips Exeter Academic Library was officially completed during my fall semester, but it was still adjusting through the winter. So, after all the classroom talks of beginnings, wonder, and silence and light, plus a class assignment on a library that spring, I had a pressing desire to see and experience Kahn’s physical interpretation of the subject. Had the spirit embedded in his personal vocabulary also reached an architectural presence? My first visit to Exeter has lived with me since, not only as a strong memory, but also as a guideline for my own practice and teaching as an architect. It triggered a strong belief in architecture and in the importance of daylight in architecture.

Daylight served as an inspirational guideline in all of Kahn’s work; it was part of his spatial search. He put his trust in light perceived as a mass, and that this would have the capacity to activate spatial intentions. If a particular light imagined through an idea seemed to be in harmony, then it followed that the rooms and their form would also be true to the situation. This was far more an important issue than the required lumen or approved lighting in relation to a particular room. In class, he often brought up that to experience a room fully, its light should come as a surprise, not anticipated, rather light discovered anew.

The Phillips Exeter Library reveals a classical timeless architecture. Situated near the centre of the high school campus, surrounded by old mature trees, the library stands out, powerful, but not incompatible with the pre-existing Neo-Georgian brick school buildings scattered across this small semi-urban setting. A number of new buildings have been erected over the years, and the scale of the campus has altered. Yet, even today, it is impossible to miss the library’s strong presence. The beautiful masonry façade sets a structural order.

Each of the brick piers emphasises a connection to gravity. The load increases incrementally, and as the piers approach the ground level, they grow thicker and the horizontal Jack arches pressed against the shape of the passing piers define the height of the openings in the walls. It all looks familiar, but on careful investigation of the façades, one notices the specificity of each level; each opening for daylight tells a story of its own. The smaller windows with the shutters indicate individual intimate spaces, different from the larger vertical windows that signal two-storey spaces. There is a clear intention to connect the exterior of the building with what unfolds inside, but also to make a connection to the ground and sky. Where the building seemingly meets the sky there is a spatial situation, and where the building connects to the ground, an arcade is on offer. When first approaching the building, one’s attention is drawn to the ground floor arcade and how the structure generates a rhythm of light and shadow. Inside this rhythm set by the masonry structure, a visitor is invited to walk around the building in search of an entrance, but for the student who lives full-time on campus, it is shelter, a meeting place, and a well-used path towards an entrance. Kahn often commented that one should discover the entrance, a journey along a path, rather than being directed to an entrance door.

Walking under the library arcade at ground level, one is aware of how the building sits in the landscape, its weight. A similar arcade space crowns the top of the building, but this unfolds with a very different light condition, as the roof is open and forms a relationship to the sky and a distant landscape. Surrounded by light, yet protected by shadow, the spatial light situation of the library’s ground floor arcade can be found in many of Kahn’s buildings. To walk outside under the large vaults at the Kimbell Art Museum in Texas is another example of this form of shaded light set by a spatial situation and its structure.

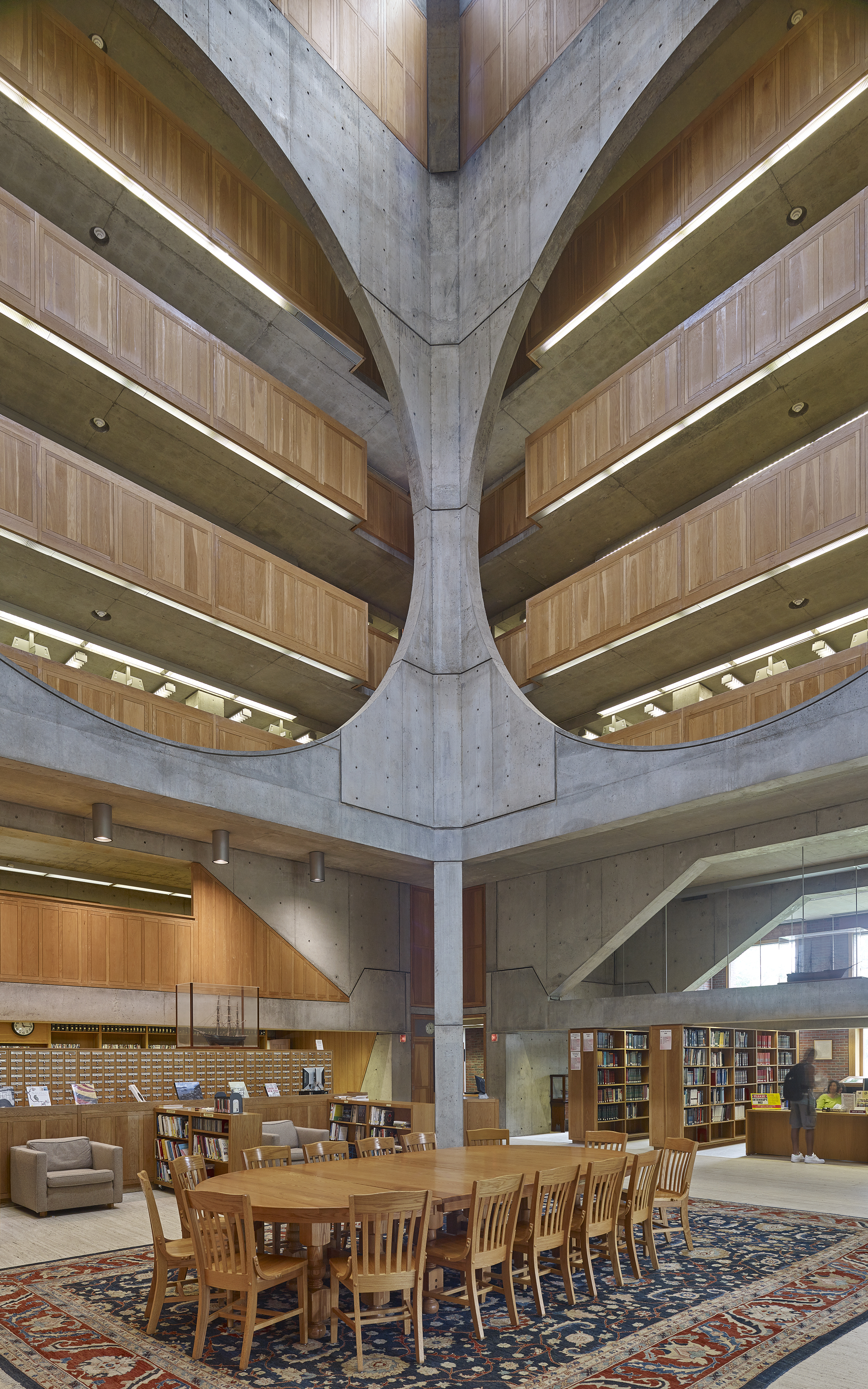

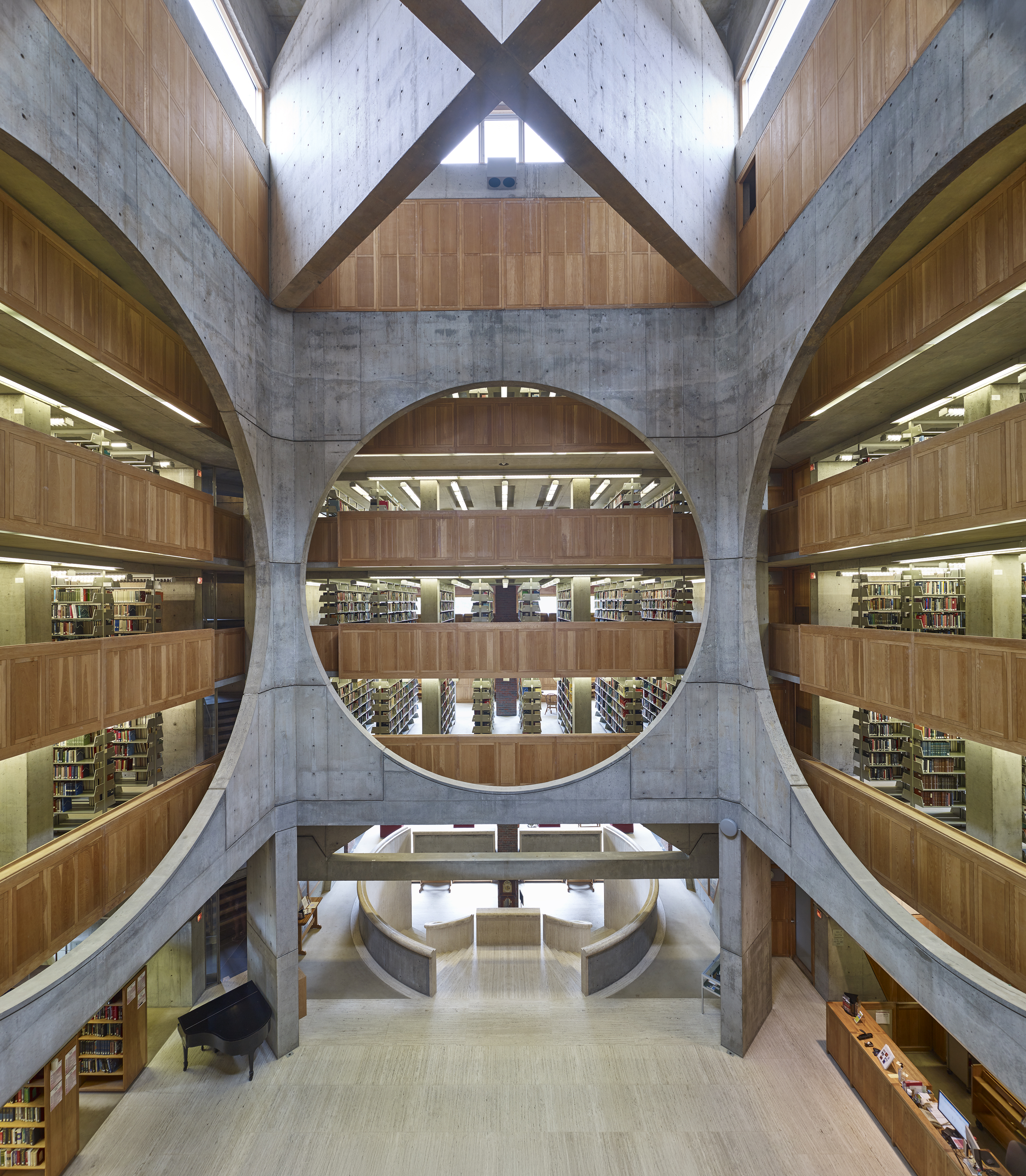

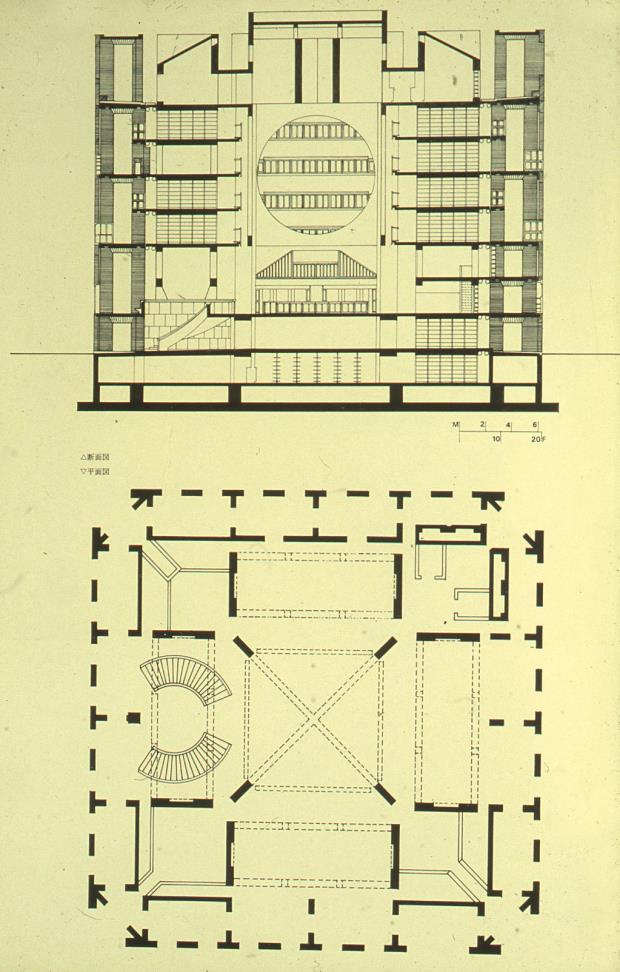

Upon entering the entrance hallway, a half-circular stairwell of concrete with travertine railing meets the visitor. Kahn felt these two materials worked well together, as they shared, on one level, similarities of surface and the reflected light would animate their textures. Before ascending the stairs, one can pause in the area for newspapers and magazines off the hallway, but the attraction of the stairwell is strong, and one is quickly wrapped up in its spatial sequence. At the top, an uplifting, singular central hall space takes one by surprise. Immediately, one is part of a library, as voices are whispers and the pace slows down. One enters a different time aspect where light and sound reach a heightened connection. The central hall is formed by independent concrete structures that frame the periphery of this square hall, and its section reveals the total height of the building. Each of the four concrete walls has a large circular opening. This gives visual and spatial contact with the rooms lying deeper inside the building, but they all relate on some level to the central square and the circular openings.

The interior is lit from above, as daylight enters from all directions through a band of glass under the roof slab. The light as a mass strikes a cross of two eighteen feet concrete beams, and from this point, it is then filtered down into the large central hall. It is not a strong light. Weakened as it reflects its way down into the hall, the light is experienced as diffuse and tranquil. Natural light also works its way in from the outer façade openings in varying strengths and character.

However, one is aware that the main source is from above, the ever-changing daylight offered through structure. It is a powerful encounter, filled with spatial energy.

The large circular openings connect the internal library functions and activities with the central hall, and one is tempted to explore further, but as a visitor, one is merely a viewer grasping the day. His or her first impression of this hall is usually a one-off experience, tied to a specific time of day and season. The students and library staff pass through this hall many times throughout the year, and this heartbeat of the library is their everyday situation. Thus, the student’s perceptions and memories of this space carry a multitude of daylight/spatial situations, which in turn connect to life on campus and the emphasis upon learning. During the second semester in Kahn’s class, we were given the library assignment, and Kahn often talked about the librarian; what kind of space a librarian needed? His reflections were directed towards spatial qualities and light pushing us to envision the user, the inhabitant’s space, in which the librarian had an essential role. There was a direct focus upon the space and its light framed as an opportunity to think and reflect: this space and light belong to the students and librarian.

In class, Kahn talked about core library identities: of spaces that connect to one’s eyes and ears, of light and sound, of reading and listening. The storyteller or reader, the table with books on display, a piano concert that fills the building, or on a cold day, the third-floor fireplace alight, all these elements generate a social awareness that indicate one is not alone. The central hall with its soft ever-changing light is a social space, but social in a reflective mood. Keep in mind that the students boarding here are young, from 9th to 12th grade, thus these small gestures which find expression through the architecture have importance and meaning in this particular environment. The interior is not the bright noisy canteen or an extension of a messy dormitory common room, but a haven of peaceful half seclusion in a public space. The library generates a sense of collective social consciousness, but it is a quiet and reflective collective, and Kahn’s use of daylight was pivotal in reaching this particular spatial mood and identity.

The central hall expresses a sense of architectural nature, where the relationship between daylight, structure, and material are the substance that forms this built nature. Set behind the large circular openings, oak panel railings enclose each floor. The honey-coloured wood reflects light differently than the concrete, but just as in his use of concrete and travertine, concrete and oak work together by way of their contrast, highlighting a warm interior light.

Kahn was particularly aware that each material responds to daylight differently, and that precision within the detailing was crucial in attaining a positive result.

His material vocabulary was usually set early in the process, and from this point, he could concentrate on the form of the space and its daylight. The Exeter library is an example of this.

In this architecture, there is a pause on offer through the daylight encountered in the central hall of the library, and this pause can be experienced in several of Kahn’s works. Completely different from Exeter, the same sense of a reflective pause can be felt in the large open space between the laboratory towers at Salk Institute. There, one faces light as a mass where nature and the room set by architecture play equal roles. At Exeter, one also participates inside light as a mass, but nature is only represented through this same daylight. However, the openness and invitation to wonder remains the same in both places.

The central hall carries a structural identity of its own, but one is quickly aware of other structural sequences that run deep into the section of the building. Upon leaving the lofty central space, one enters the darker spatial zone of the book stacks, which reside in a separate concrete structural element, and then moves on towards the light of the outer spatial layer and its light. This twelve-foot deep brick structural, spatial layer offers a variety of places to sit, contemplate or read, and exemplifies Kahn’s quote:

“A man with the book goes to the light. A library begins that way.” ¹

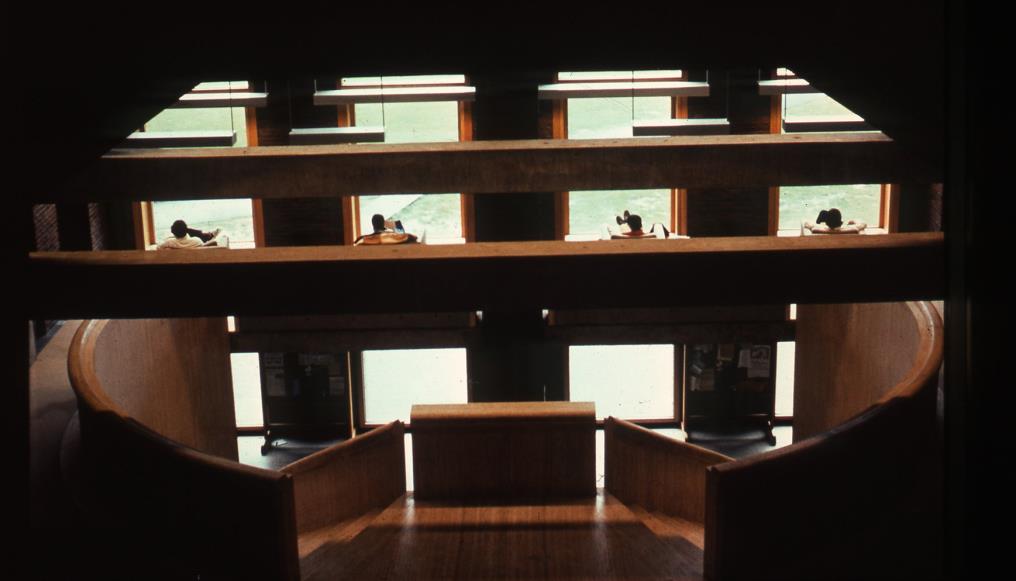

Here in this reading zone filled with daylight, one may sit on the travertine bench set between the brick arches or choose a comfortable chair close to the outer two-storey wall.

However, the areas for bookshelves have single-storey heights, thus creating mezzanine floors overlooking the reading areas on the main floor and farther up overlooking the study carrels along the windows. Each carrel is a room in itself; slightly enclosed desks with shutters facing the windows allowing students to control the amount of light specific to the time of day, need and mood. During my first visit, these carrels had nametags, photos and sketches indicating a private space, and yet they were still public. Each of the various reading or study areas offer a clear light identity. Where to sit or what to do where, is not an indifferent choice. The single book stacks tucked into the concrete structure have a dim refracted light, but as one moves out towards the lofty reading zone or farther up to the study carrels, the light changes as it reflects off the oak panelling. Each space allows for study, reflection, and concentration, but there is also an elasticity within this function, which gives a student a sense of connection to others.

Kahn was also occupied with the need for a pause in relation to student wellbeing, and he regarded the central hall as a trigger to such an effect. If tired of reading or in search of company one could leave the study carrel along the outer rim, walk through the book stacks, and reach a perfect view over the hall from the oak railings that skirt each floor around the hall. From here, there is a connection with the comings and goings and all the activities in the main central hall. In addition, a wide shelf runs the length of the railing where people can browse through strategically placed large picture books while keeping an eye on activity below. From this viewpoint, the light is a refracted yet dense light, quite different from that of the reading rooms and study carrels along the rim. The intensity of daylight as one nears the oak railings above the hall is dependent upon where one is in the section.

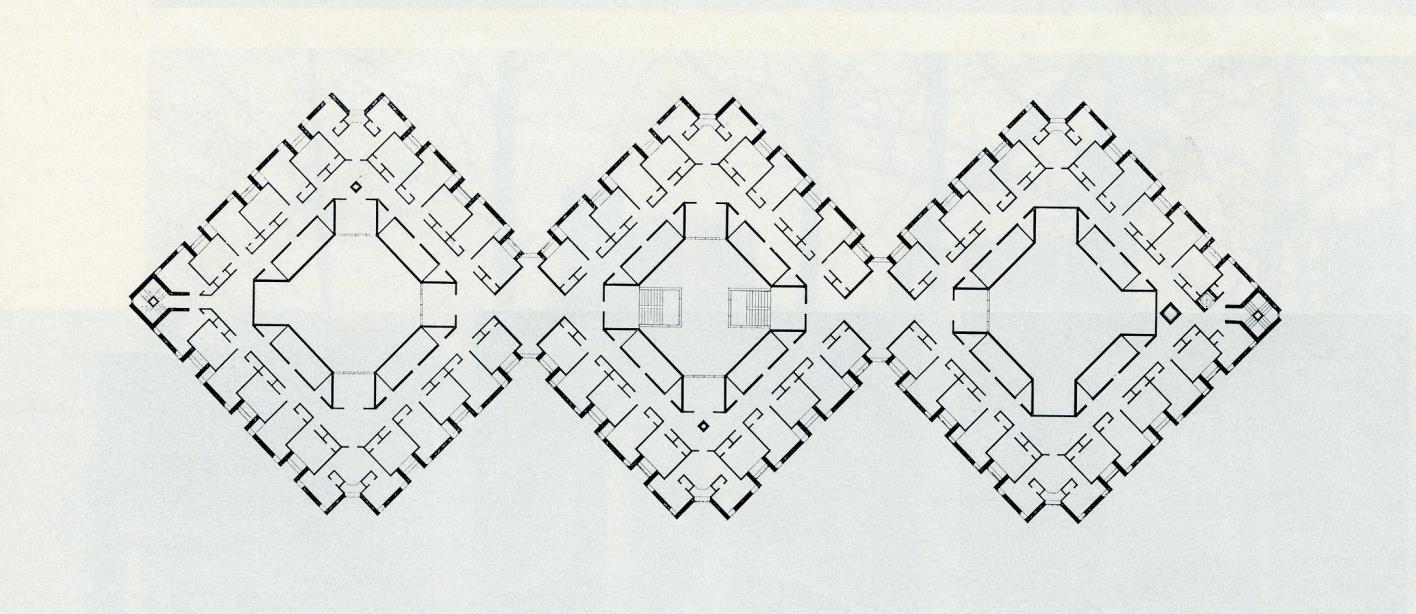

Kahn’s interpretation of connection, how one wall meets another wall, is interesting in relation to his use of daylight. It is not always a true connection, in that the walls do not touch, thus creating a space in-between that bares an identity of its own. The connections between the three quadrate volumes in the Eleanor Donnelly Erdman Hall Dormitory, Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania (1960-65) are an example of this. In the library, the corners adjacent to the book stack zone carry a spatial identity of their own. These are service spaces containing stairs, elevators, restrooms and technical installations. Kahn insisted that spaces that serve a building should not be neglected or receive less care. Each of the three light zones has their specific structural identity. This is best revealed through the section, but by walking through the section, one becomes aware of an in-between structural layer, an interstitial space where the ducts for ventilation and other mechanical necessities find their path. They do not disturb or interfere with the identity of the rooms for humans, yet still participate in the reading and understanding of the building as a whole.

However, in relation to light, it is more interesting to look at how Kahn spatially cut off the corners of the reading zone, and by so doing forms each corner into an open balcony to the outside. The daylight that enters these corners also enters the reading and study rooms. The glass door and window above the door run floor to ceiling allowing the full strength of light into the zone, which in turn blends with the light from the façade openings giving a mixed light of different intensities.

If there is too much stress or a need for a pause, retreat is possible through the open corner balcony, to take in light, and air, and at the same time view the surrounding urban landscape. One is never trapped. The garden arcade at the top of the building, signals even more freedom. On this level, there is a direct connection to the sky and a view of the distant landscape. In addition, the rare book collection is here, secure, protected from direct light, and yet there is a table upon entry which welcomes one to sit down and read. Here, a shaft of natural light changes throughout the day.

For Kahn, this relationship between structure, material, and daylight relates to his core approach to architecture. Despite numerous, beautifully built works, this three-part relationship is most clearly expressed in the Exeter Library. The building has a logic. One does not have to be an engineer to understand how the different building components work together. The physical room and its structural identity are one and the same, and the mass that gives the room its particularity is shadow and light. Each of the three major structural identities are complete in their specificity and precision. There is nothing to add or take away, but as place, it longs for a human connection. What is shared between the student/staff who visit daily, and the occasional visitor, is a spatial reference, a mood and energy that is sensed by everyone. In many ways, this is the social awareness Kahn so earnestly argued for in his use of the term Institution.

“For him the institution of man embodied a collective recognition of essential human values, a consensus that is intuitively apparent long before the more circumstantial material demands of life begin to have an impact.” ²

It is an architecture where one is never left behind nor is it an architecture that highlights a material or detail intensity with an orientation to focus on the architectural object. Kahn’s Exeter library is not about that, but rather a search for a strong and positive relationship between body and space on an individual level, but also as a collective. The fundamental aim was to inspire young students to study. Since the building never compromised its function nor its identity, the library is still a place to read, think and contemplate. Kahn’s use and belief in the importance of daylight as a material seems absolute. In class Kahn commented that, “light was the very source of matter itself” that “light that has ceased to be light becomes material” and that “all material cast shadow, thus it belongs to light.”³ The reason for including this quote is to emphasise that for Kahn the use of daylight was not a matter of choice, but deeply embedded in the core of his creative process. It was a focus from the beginning to the end. In the Exeter library, one feels the essence of this search.

For some time, there has been an ongoing discussion related to the identity of the ‘New Library’ – the new social arena. Bookshelves and archives may still be an integral part of a library, but the focus is upon places to meet and mingle, the coffee shop, the lecture hall, exhibition space and not in the least the plethora of technological gadgets. The library setting and its space, which once signalled reflection, study and concentration has shifted, the institution has changed. Perhaps, its spatial identity is now closer to many other public spaces. The net has challenged our earlier physical connection to the book and the need for a place to read and study. This is interesting in that the social reading of a library’s agenda and its content is so strong and clear in its brief that it has changed the core idea of a library from a formal quiet institution to a casual meeting place for many activities, including books. The ‘New Library’ directs attention towards the spatial complexities and uncertainty of our present situation where most books, all facts, and news are only a key stroke away, seconds from all places, from anywhere. There is an ongoing discussion about what these changes mean, positive or negative, and how technology has gradually taken over much of daily life. This will certainly challenge the relationship Kahn called Knowledge and Knowing. “Knowing which referred to the personal lived experience rooted in the character of the individual…the way we are made. Knowledge reflects nature’s laws and belongs to everything related to the universe.”⁴. In a sense, knowledge is what we learn from others. The question one might ask in relation to the New Library situation is whether it stimulates knowing and the individual creative thinking. Many still believe this is dependent upon the ability to concentrate. Where will this take place, what is this space?

Architecture has the capacity and ability to connect life’s changes, trends and even deep cultural shifts into a physical spatial expression. In this is great responsibility as an architect. Not all trends or changes are necessarily more than short-term infatuations, but the responsibility tied to building is a long-term commitment. It is not easy to find a balance between past and present, to follow or disagree on numerous changes or popular ad-hoc trends. Kahn had the ability to find balance, as he was always in search of a common human factor, a spatial content, which over time would continue to belong to everyone. This spatial content has the capacity to take on transformation; an order embedded in the room itself.

Returning to the Exeter library, it offers room for concentration, to read and to reflect, and yet, it clearly has a social dimension. The key thing is that these two activities are coexisting, as the architecture and the light of a quiet place set comprehensible links and limits. One is not alone, and at the same time, the individual experience of reading is not diminished or curtailed in this environment. The library refrains from becoming a public stage, rather offering a place to discover the world anew through books, but this also occurs through technology, as laptops and other instruments have long inhabited Exeter library. However, for all the changes, the room and its light have not succumbed, as the library remains a place for concentration, meaning a deeper dive into exploration and invention related to knowing: to read and to contemplate.

The human reads in the light.

References

1. Kahn, L. I. (1957). The continual renewal of architecture comes from changing concepts of space. Perspecta, 4, 1-12.

2. Fjeld, P. O., Fjeld, E. R., & Kahn, L. I. (2019). The Nordic latitudes. University of Arkansas Press. p.191

3. Ibid, pp. 184-85

4. Ibid, p. 182